Dental Caries (Cavities) Comprehensive Review

Frisco Kid’s Dentistry has added “Dental Caries (Cavities) Comprehensive Review” for parents and colleagues seeking a more in-depth understanding of cavities. Treatment for cavities is geared towards prevention by dietary modification and good dental hygiene, since there is no known method to regenerate large amounts of damaged or missing tooth structure.

What are Dental Caries (Cavities)?

Dental caries (from the Latin, “rot”), also known as tooth decay or a” cavity”, is a bacterial infection that causes demineralization and destruction of the hard tissues of the teeth (enamel, dentin and cementum). It is a result of the production of acid by bacterial fermentation of food debris accumulated on the tooth surface. If factors causing demineralization of teeth (i.e. carbohydrates, dry mouth and plaque) exceed factors, which help remineralize teeth (i.e. saliva, calcium, and fluoride), tooth decay will occur. In regards to occurrence, dental decay is the most common chronic disease in childhood. The American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry reports that 60% of children experience tooth decay by the age of five.

Dental caries (from the Latin, “rot”), also known as tooth decay or a” cavity”, is a bacterial infection that causes demineralization and destruction of the hard tissues of the teeth (enamel, dentin and cementum). It is a result of the production of acid by bacterial fermentation of food debris accumulated on the tooth surface. If factors causing demineralization of teeth (i.e. carbohydrates, dry mouth and plaque) exceed factors, which help remineralize teeth (i.e. saliva, calcium, and fluoride), tooth decay will occur. In regards to occurrence, dental decay is the most common chronic disease in childhood. The American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry reports that 60% of children experience tooth decay by the age of five.

Signs and Symptoms of Dental Caries (Cavities)

Without routine dental examinations, most people first become aware of tooth decay when they begin to feel pain. Unfortunately tooth pain is most often only felt once the decay has penetrated fairly deep into tooth structure. A person experiencing caries may be unaware of the disease until a significant amount of the tooth has been affected. The earliest sign of decay is the appearance of a chalky white spot on the surface of the tooth, indicating an area of enamel demineralization. This is referred to as a white spot lesion, or a “microcavity.” As the area continues to lose minerals it can turn brown and eventually cave in, forming a cavity. Before the cavity forms, the process is potentially reversible through remineralization. However, once a cavity forms, the lost tooth structure cannot be regenerated. Dark brown spots may indicate previous demineralization. Active decay is lighter in color and dull in appearance.

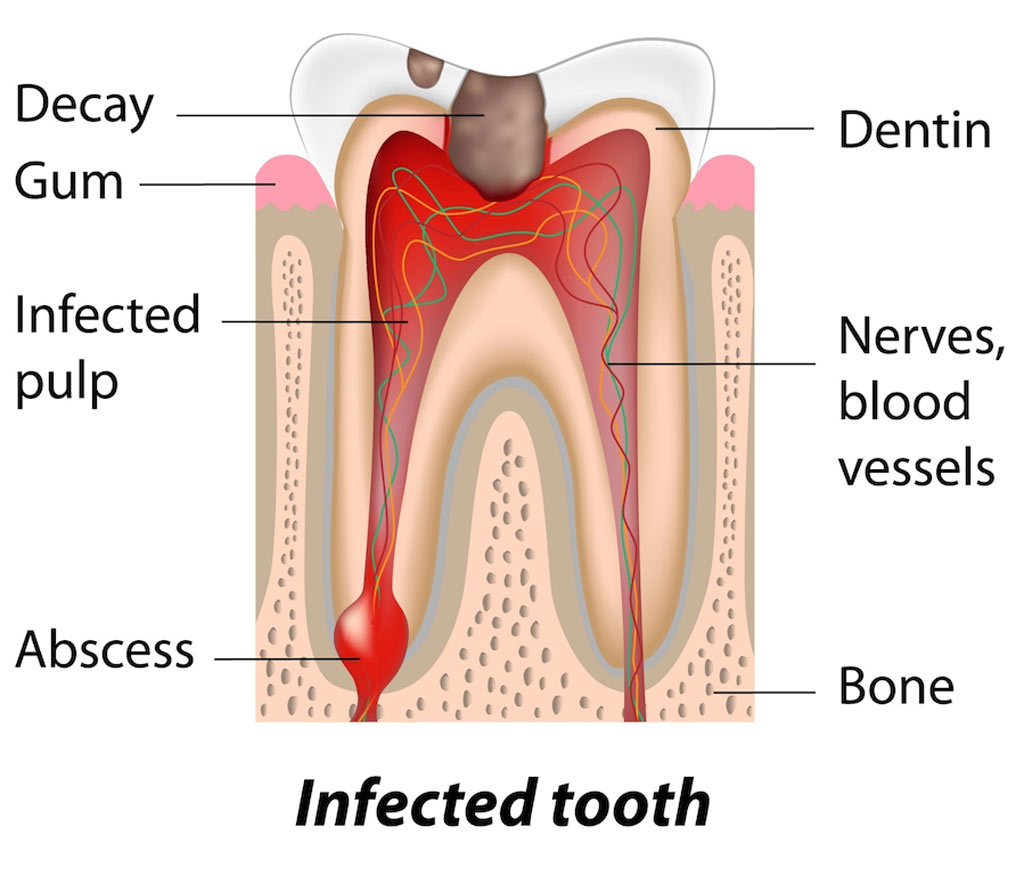

As the layers of the tooth are damaged, the cavity becomes more noticeable and the affected areas of the tooth change color and become softer to dental probing. Once the decay passes through enamel, the dentinal tubules, which have passages to the nerve (pulp) of the tooth, become exposed, resulting in pain. A tooth weakened by extensive internal decay can fracture under normal chewing forces. When the decay has progressed enough to allow the bacteria to penetrate the pulp a toothache can result and the pain will become more constant. Necrosis (death) of the pulp tissue and infection are common consequences of untreated dental decay. Once the pulp tissue has undergone necrosis the tooth will no longer be sensitive to hot or cold, but can be very tender to pressure. Dental caries can also cause bad breath and foul tastes in the mouth.

Causes of Dental Caries

Causes of Dental Caries

There are four factors necessary for caries to form: a tooth surface (enamel or dentin), caries-causing bacteria, fermentable carbohydrates (such as sucrose), and time. Even with these present, however, caries may not occur. There is not an inevitable outcome and people differ in susceptibility based on several factors, such the shape of their teeth, oral hygiene habits, frequency of carbohydrate intake, and the buffering capacity of their saliva. Caries can occur on any surface of a tooth that is exposed to the oral cavity.

The bacteria most responsible for dental cavities are Streptococcus mutans, Streptococcus sobrinus, and lactobacilli. Bacteria are one of the main components of plaque which is simply a sticky “soup” of bacteria, food and saliva. These bacteria cause disease in the presence of fermentable carbohydrates such as sucrose, fructose, and glucose. Teeth are sensitive to destruction when the pH of their direct environment falls to 5.5 or below. This is known as the critical pH and signifies and an acidic environment. Saliva raises the pH (decreases the acidity) and thus is vital in remineralization. Because of this, conditions or factors that lead to decreases salivary flow can increase one’s susceptibility to caries. Most disease (80%) occurs in areas unreachable with a toothbrush, such as between teeth and inside very small pits and fissures in the teeth

Some foods or beverages themselves have a pH of 5.5 or lower which can result in demineralization in the absence of bacteria. This is known as erosion, rather than caries, because the acid is not bacterial in origin. Frequent regurgitation of stomach contents (reflux disease or bulimia) can also contribute to erosion by lowering the pH of the mouth.

Congenital Enamel Defects

There are some extremely rare conditions where the enamel of the teeth is either imperfectly formed or made in smaller amounts. These patients are thus congenitally susceptible to increasing chances of caries and tooth damage.

Approximately 96% of tooth enamel is composed of minerals. As previously stated these minerals, especially hydroxyapatite, dissolve when exposed to acidic environments (pH less than 5.5). The inner layers of the teeth, dentin and cementum are more susceptible to caries than enamel because they have lower mineral content. Mouth anatomy may also play a small role in the development of caries – misaligned teeth may result in more food being trapped between them.

Mouth Bacteria

While the mouth naturally has many varieties of bacteria, the ones most commonly attributed to forming caries are Streptococcus Mutans and Lactobacilli. These strains of bacteria appear to form high levels of lactic acid as a byproduct of breakdown of dietary sugars. Infants are born without this bacterium in their mouths but are usually inoculated by the primary care giver (i.e. mom or dad). It is for this reason that it is discouraged to share utensils with young children, as this can facilitate the transmission of cavity forming bacteria. Bacteria most often accumulates in areas that are more difficult to brush (pit and fissures of the biting surface of molars) or in the small pockets formed where the teeth insert into the gum tissue (sulcus). Plaque may also collect below the gum line. Plaque buildup not only increases the risk of decay but can also lead to gum inflammation or bone loss. Studies have also shown that higher levels of bacteria in the mouth can lead to increased risk of diseases in other parts of the body including the heart.

Cavities Due to Fermentable Carbohydrates

Bacteria in a person’s mouth convert common sugar into acids through a process called fermentation. If left in contact with the tooth, these acids may cause demineralization, which can eventually lead to formation of a cavity or hole. The impact such sugars have on the progress of dental caries is called carcinogenicity. Sucrose seems to be more cariogenic than glucose or fructose.

Dental Acid Exposure Causing Cavities

The frequency of which teeth are exposed to cariogenic (acidic) environments affects the likelihood of caries development. After meals or snacks, the bacteria in the mouth metabolize sugar, resulting in an acidic by-product that decreases pH. As time progresses, the pH returns to normal mostly due to the buffering capacity of saliva. During every exposure to the acidic environment, portions of the inorganic mineral content at the surface of teeth dissolves and can remain dissolved for two hours. Since teeth are vulnerable during these acidic periods, the development of dental caries relies heavily on the frequency of acid exposure.

The caries process can begin within days of a tooth’s eruption into the mouth if the diet is sufficiently rich in suitable carbohydrates. Evidence suggests that the introduction of fluoride has slowed the process of caries formation. Interproximal caries (caries in between teeth) take an average of four years to pass through enamel in permanent teeth. Because the cementum enveloping the root surface is not nearly as durable as the enamel encasing the crown, root caries tends to progress much more rapidly than decay on other surfaces. The progression and loss of mineralization on the root surface is 2.5 times faster than on enamel. In very severe cases, where oral hygiene is very poor and where the diet is very rich in fermentable carbohydrates, caries may cause cavities within months of tooth eruption. This can occur, for example, when children continuously drink sugary drinks from baby bottles

Other Factors Causing Cavities

Reduced salivary flow rate is associated with increased caries since the buffering capability of saliva is one of the best natural defenses to tooth demineralization. As a result, medical conditions that reduce the amount of saliva produced by salivary glands, in particular the submandibular gland and parotid gland, can lead to widespread tooth decay. Examples include Sjögren’s syndrome, diabetes mellitus, diabetes insipidus, and sarcoidosis. Medications, such as antihistamines and antidepressants, can also impair salivary flow. Stimulants, most notoriously methylamphetamine (“meth mouth”), also severely occlude the flow of saliva.

Tetrahydrocannabinol, the active chemical substance in cannabis, also causes a nearly complete occlusion of salivation, known in colloquial terms as “cotton mouth”. Radiation therapy of the head and neck may also damage the cells in salivary glands, decreasing output. There is also evidence suggesting that smoking may increase the incidence of caries.

Intrauterine and neonatal lead exposure has been shown to promote tooth decay. In addition to lead, all atoms with electrical charges similar to bivalent calcium mimic the calcium ion and therefore exposure may promote tooth decay.

Poverty is also a significant social determinant for oral health. Dental caries have been linked with lower socio-economic status and can be considered a disease of poverty, largely due to poor dental hygiene.

Pathophysiology of Dental Caries (Cavities)

Enamel

Enamel is a highly mineralized acellular tissue that is broken down by the lactic acid produced by bacteria. The acid demineralizes the crystals in the enamel, allowing the bacteria physically penetrate the dentin.

Dentin

Unlike enamel, the dentin reacts to the progression of dental caries. After tooth formation, the ameloblasts, which produce enamel, are lost and thus cannot later regenerate enamel. On the other hand, dentin is produced continuously throughout life by odontoblasts, which reside at the border between the pulp and dentin. A stimulus, such as caries, can trigger a biologic response, which causes odontoblasts to produce more dentin. These defense mechanisms include the formation of changed dentin.

According to hydrodynamic theory, fluids within the dentin are believed to be the mechanism by which pain receptors are triggered within the pulp of the tooth. Since the changed dentin prevents the passage of such fluids, pain that would otherwise serve as a warning of the invading bacteria may not develop initially. Consequently, dental caries may progress for a long period of time without any sensitivity of the tooth, allowing for greater loss of tooth structure.

Diagnosis of Dental Caries (Cavities)

The presentation of caries is highly variable. However, the risk factors and stages of development are similar. Initially it may appear as a small chalky area (smooth surface caries), which may eventually develop into a large cavitation. Sometimes caries may be directly visible. However, other methods of detection such as X-rays are used for less visible areas of teeth and to judge the extent of destruction. Disclosing solutions are also used during tooth restoration to minimize the chance of recurrence.

Primary diagnosis involves inspection of all visible tooth surfaces using a good light source, dental mirror and explorer. Dental radiographs (X-rays) may show dental caries before it is otherwise visible. Large dental caries are often apparent to the naked eye, but smaller lesions can be difficult to identify. Visual and tactile inspection along with radiographs is employed frequently among dentists, in particular to diagnose pit and fissure caries. Early, uncavitated caries is often diagnosed by blowing air across the suspect surface, which removes moisture and changes the optical properties of the unmineralized enamel. At times, pit and fissure caries may be difficult to detect. Bacteria can penetrate the enamel to reach dentin, but then the outer surface may remineralize, especially if fluoride is present. [These caries, sometimes referred to as “hidden caries”, will still be visible on x-ray radiographs, but visual examination of the tooth would show the enamel intact or minimally perforated.

Classification of Dental Caries (Cavities)

Early childhood caries and rampant decay

Early childhood caries (ECC), previously known as “baby bottle caries”, “bottle rot,” is a pattern of decay found in young children with deciduous (baby) teeth. The teeth most likely affected are the maxillary anterior teeth, but all teeth can be affected. The name for this type of caries comes from the fact that the decay is commonly a result of allowing children to fall asleep with sweetened liquids (including milk) in their bottles or feeding children sweetened liquids multiple times during the day.

Another pattern of decay is “rampant caries”, which signifies advanced or severe decay on multiple surfaces of many teeth. Rampant caries may be seen in individuals with xerostomia, poor oral hygiene, stimulant use (due to drug-induced dry mouth) and/or large sugar intake. If rampant caries is a result of previous radiation to the head and neck, it may be described as radiation-induced caries.

Oral Hygiene Prevents Dental Caries (Cavities)

Personal hygiene care consists of proper brushing and flossing daily. The purpose of oral hygiene is to minimize any etiologic agents of disease in the mouth. The primary focus of brushing and flossing is to remove and prevent the formation of plaque (dental biofilm). Plaque consists mostly of bacteria and as the amount of bacterial plaque increases; the tooth is more vulnerable to dental caries when food is left on teeth after every meal or snack. A toothbrush can be used to remove plaque on accessible surfaces, but not between teeth or inside pits and fissures on chewing surfaces. When used correctly, dental floss helps removes plaque from areas that could otherwise develop interproximal caries. Other adjunct oral hygiene aids include interdental brushes, water picks, and mouthwashes.

Oral hygiene is probably more effective at preventing gum disease (periodontal disease) than tooth decay. When eating, food is forced inside pits and fissures under chewing pressure. This can lead to carbohydrate-fueled acid demineralization in areas where the brush, fluoride toothpaste, and saliva have no access to remove trapped food, neutralize acid, or remineralize tooth structure. This is called occlusal caries and may account for between 80 and 90% of caries in children. Chewing fiber like celery after eating forces saliva inside trapped food to dilute any carbohydrate, neutralize acid and remineralize tooth structure. The teeth at highest risk for carious lesions are the permanent first and second molars due to length of time in oral cavity and presence of complex surface anatomy.

Professional hygiene care consists of regular dental examinations and professional prophylaxis (cleaning). Along with oral hygiene, radiographs may be taken at dental visits to detect possible dental caries development in high-risk areas of the mouth (e.g. “bitewing” x-rays which visualize between crowns of the back teeth).

Dietary Modification for Dental Health

Frequency of sugar intake is more important than the amount of sugar consumed. In the presence of sugar, bacteria in the mouth produce acids. The more frequently teeth are exposed to this environment the more likely dental caries are to occur. Therefore, minimizing snacking is recommended, since snacking creates a continuous supply of nutrition for acid-creating bacteria in the mouth. Also, chewy and sticky foods (such as dried fruit or candy) tend to adhere to teeth longer increasing the exposure time and thus chance for caries. American Dental Association and the European Academy of Pediatric Dentistry recommend limiting the frequency of consumption of sugar-laden drinks. For young children, putting them to bed with a bottle of milk also significantly increases the change of caries formation and can be detrimental to their oral health. Mothers are also recommended to avoid sharing utensils and cups with their infants to prevent transferring bacteria from the mother’s mouth (a process known as vertical transmission).

It has been found that certain kinds of dairy products like cheddar cheese can help counter tooth decay if eaten soon after the consumption of foods potentially harmful to teeth. This is most likely due to the buffering capacity as it helps to counteract the effects of acids. Also, chewing gum containing xylitol (a naturally occurring sugar alcohol) is widely used to protect teeth in many countries now. Xylitol’s effect on reducing dental biofilm is due to bacteria’s inability to utilize it like other sugars, thus preventing the formation of bacterial acid. Chewing and stimulation of flavor receptors on the tongue are also known to increase the production and release of saliva, which contains natural buffers to prevent the lowering of pH in the mouth

The use of dental sealants is a valuable tool in caries prevention. Sealants are a thin plastic-like coating applied to the chewing surfaces of the molars to prevent food from being trapped inside pits and fissures. This deprives resident plaque bacteria of carbohydrate thus decreasing the occurrence of pit and fissure caries. Sealants are usually applied on the teeth of children as soon as the tooth erupts but may also benefit adults if not previously placed. Sealants can wear over time and may need to be replaced so dental professionals must check them regularly.

Calcium, found in milk and green vegetables, is often recommended to protect against dental caries. Fluoride helps prevent decay of a tooth by binding to the hydroxyapatite crystals in enamel and strengthening it. Once the fluoride is bound, the tooth surface is less susceptible to demineralization and decay. Incorporated calcium also makes enamel more resistant to demineralization. Topical fluoride is now more highly recommended than systemic intake. This may include a fluoride toothpaste, mouthwash or professionally applied varnish. After brushing with fluoride toothpaste all excess toothpaste should be spit out but rinsing with water should be avoided. This leaves a greater concentration of fluoride residue on the teeth. Many dental professionals include application of topical fluoride solutions as part of routine visits and recommend the use of xylitol and amorphous calcium phosphate products. Research is currently being conducted on the formation of a possible “caries vaccines” and initial findings are promising.

Treatment Dental Caries (Cavities)

Treatment is primarily based on whether cavitation is present or not. Noncavitated lesions can be arrested and remineralization can occur under the right conditions. However, this may require extensive changes to the diet (reduction in frequency of refined sugars), improved oral hygiene (tooth brushing twice per day with fluoride toothpaste and daily flossing), and regular application of topical fluoride. Such management of a carious lesion is termed “non-operative” since no drilling is carried out on the tooth. Non-operative treatment requires excellent understanding and motivation from the individual, otherwise the decay will continue.

Once a lesion is cavitated, especially if dentin is involved, a dental restoration is usually indicated (“operative treatment”). Before a restoration can be placed, all of the decay must be removed to prevent progression of the disease process underneath the filling. Sometimes a small amount of decay can be left if it is entombed and there is a seal, which isolates the bacteria from their substrate. Techniques such as stepwise caries removal are designed to avoid exposure of the dental pulp and decrease the amount of tooth substance, which requires removal before the final filling, is placed. Often enamel, which overlies decayed dentin, must also be removed, as it is unsupported and susceptible to fracture.

Destroyed tooth structure does not fully regenerate, although remineralization of very small carious lesions may occur if dental hygiene is kept at optimal level. For the small lesions, topical fluoride is sometimes used to encourage remineralization. For larger lesions, the progression of dental caries can be stopped by treatment. The goal of treatment is to preserve tooth structures and prevent further destruction of the tooth. Completed fillings should be regularly examined by a dental professional to ensure integrity.

Treatment Modalities For Dental Caries

In general, early treatment is quicker and less expensive than treatment of extensive decay. Local anesthetics, nitrous oxide (“laughing gas”), or other prescription medications may be required in some cases to relieve pain during or following treatment or to relieve anxiety during treatment. Additionally, young patients with severe dental anxiety, extensive treatment needs, or with special health care needs may require treatment to be completed with the use of in-office IV sedation or general anesthesia in a hospital setting. A dental hand-piece (“drill”) is used to remove large portions of decayed material from a tooth. A spoon, a dental instrument used to carefully remove decay, is sometimes employed when the decay in dentin reaches near the pulp. Once the decay and damaged tooth structure is removed, a dental restoration of some sort is placed to return the tooth to function and aesthetic condition.

Treatment Materials

Restorative materials include dental amalgam, composite resin, stainless steel crowns, porcelain, and gold. Composite resin and porcelain can be made to match the color of a patient’s natural teeth and are thus used more frequently when aesthetics are a concern. In cases where the decay has severely undermined and weakened the tooth structure, a filling may not be an appropriate treatment option. These teeth will require placement of a crown, which surrounds the tooth and allows it to withstand the biting forces during normal chewing and function.

In certain cases, endodontic therapy may be necessary for the restoration of a tooth. Endodontic therapy, also known as a “root canal”, is recommended if the pulp in a tooth dies from infection by decay-causing bacteria or from trauma. During a root canal, the pulp of the tooth, including the nerve and vascular tissues, is removed along with decayed portions of the tooth. The canals are instrumented with endodontic files to clean and shape them, and they are then usually filled with a rubber-like material called gutta percha. The tooth is filled and a crown can be placed. Upon completion of a root canal, the tooth is now non-vital, as it is devoid of any living tissue. In primary (baby teeth) sometimes a “pulpotomy” will be performed. In these cases the bacteria has invaded the coronal portion of the tooth’s pulp but has not affected the pulp in the roots. For these teeth, the coronal pulp is removed while the remaining healthy root pulp is maintained. The coronal portion is then filled with restorative material and a crown is placed over the tooth.

An extraction can also serve as treatment for teeth with severe dental caries. The removal of the decayed tooth is performed if the tooth is too far destroyed from the decay process to effectively restore the tooth. Extractions are sometimes considered if the tooth lacks an opposing tooth or is likely to cause problems or complications in the future, as may be the case for wisdom teeth. Extractions may also be preferred by patients unable or unwilling to undergo the expense or difficulties in restoring the tooth.

Causes of Dental Caries

Causes of Dental Caries